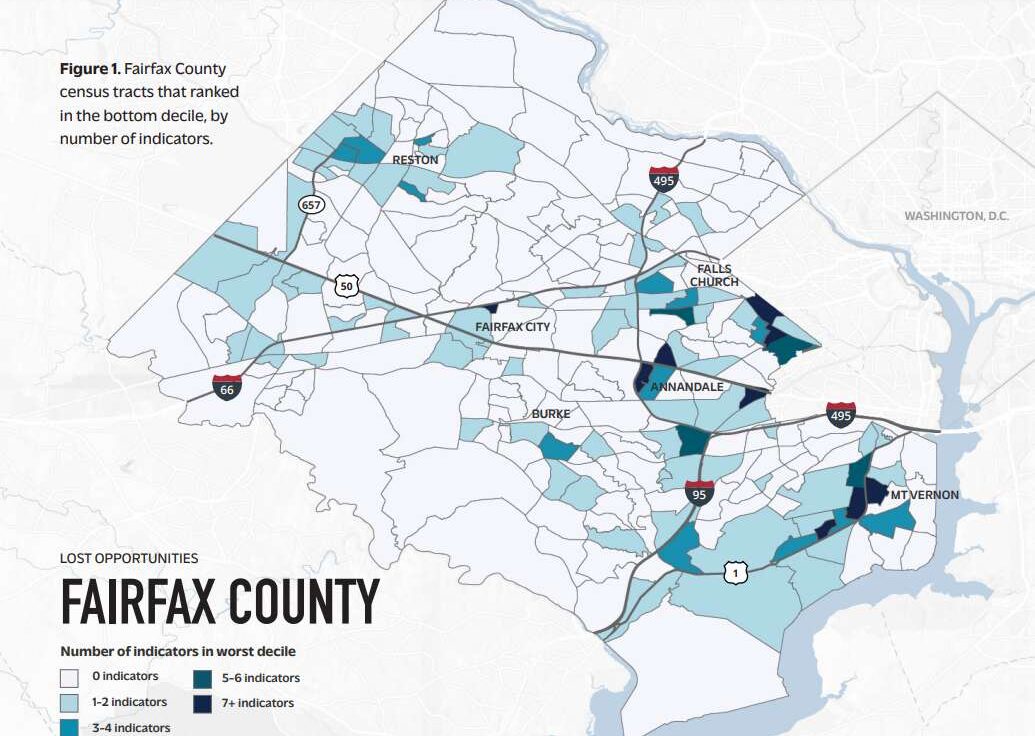

In between the sprawling lawns of Loudoun County and the riverside lofts of Alexandria lie clusters of struggling, predominantly non-white neighborhoods that are increasingly left out of the success and prosperity experienced by Northern Virginia as a whole, recent research notes.

In fact, conditions in some of those neighborhoods — called “islands of disadvantage” — have been in decline for years.

According to a new report by the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, poverty, rates of people without health insurance, educational attainment, job opportunities and overcrowding all worsened in those neighborhoods between 2013 and 2021.

At the same time, the report notes the economic progress seen in some areas was also accompanied by gentrification and displacement of people of color.

“What is otherwise a healthy and wealthy area is also home to areas of concentrated disadvantage,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, lead author of the VCU report. “This is not something that is widely known, that people are living in deep poverty just a short distance away from the McMansions and golf courses.”

The report, “Lost Opportunities: The Persistence of Disadvantaged Neighborhoods in Northern Virginia,” compares census data from 2009-13 and 2017-21 for Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun and Prince William counties and the city of Alexandria to understand the social and economic changes the region has experienced over time.

The report, commissioned by the Northern Virginia Health Foundation, builds upon previous research led by Woolf that showed the disproportionate amount of non-white residents that make up struggling neighborhoods experience substantially higher rates of premature death compared to Northern Virginia as a whole.

The latest research found that between 2009-13 and 2017-21, 92% of Northern Virginia census tracts saw an increase in median income, 73% had a rise in residents with a bachelor’s degree and 59% experienced gains in the proportion of adults with a high school diploma. Poverty and uninsured rates decreased in 52% and 78% of the region’s census tracts, respectively.

However, some “islands of disadvantage” experienced opposite trends during those time periods. One section of Bailey’s Crossroads in Fairfax County saw median household income decrease by about $10,000, child poverty rates nearly double to 63% and the overall poverty rate climb to 30%. Read More

Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares announced [on Tuesday] the commonwealth is joining 32 other states in a federal lawsuit against Meta over allegations its social media platforms are purposely harmful to children.

The lawsuit alleges that Meta knew about the extent of the psychological and health harms suffered by young users addicted to its platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, but falsely assured the public they are safe and suitable for children and teens.

It also claims Meta’s business model exploits and monetizes young users through data harvesting and targeted ads by designing purposely-addictive platform features.

The suit alleges features such as auto-play, algorithms and near-constant alerts were knowingly created with the express goal of hooking children and teens into descending “rabbit holes.” In turn, the suit claims young users can be exposed to harmful content such as suicide and self-harm content, hate speech and misinformation.

The suit claims Meta also has a “deep understanding” of the significant and extensive harms to young people associated with addiction and compulsive use of the platforms, including depression, eating disorders, physical self-harm and suicidal ideation.

Miyares compared Meta to big tobacco companies advertising to children, pointing to the Joe Camel cartoon as a way to hook young people on cigarettes.

“At the expense of public health and specifically the health of our youth, they’ve exploited the vulnerability of our young children and the fundamental desire for connection for their own personal gain,” Miyares said during a press conference on Tuesday.

Additionally, the suit alleges Meta is well aware that kids under the age of 13 are on their platform, but still collects data from these children without first obtaining verifiable parental consent as required by the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.

Miyares said that Meta could obtain parental consent using age verification technologies, like uploading a drivers license or official government identification. When asked about the potential for data breaches seen in states requiring third-party age verification methods to access pornographic websites, Miyares reiterated the technology is a great first step to protecting children.

“Let’s try to protect our kids, let’s try to protect their innocence and let’s make sure parents are involved and parents matter,” Miyares said.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin has previously expressed similar concerns that parents need to be more involved in efforts to mitigate the impact of social media on children and teenagers.

Youngkin proposed an amendment to Virginia’s pornographic website age verification law that would have extended the age of children who require parental consent for social media accounts from under 13 to under 18. The Senate narrowly rejected the proposal.

At a “Parents Matter” town hall this August, Youngkin heavily emphasized the importance of parents’ involvement in their child’s social media life.

Miyares said he hopes Meta complies with consumer protection laws and prioritizes the safety of children moving forward, and if not, he isn’t afraid of the fight.

“We would welcome the opportunity to have a meaningful discussion about how they could change their platforms to better protect our children and our teens,” Miyares said. “You chose to fight us, we’ll see you in court.”

Image via Brett Jordan/Unsplash. This article was reported and written by the Virginia Mercury, and has been reprinted with permission.

Halfway through Virginia’s review of whether millions of Medicaid enrollees are still eligible for coverage after the pandemic, nearly 160,000 Virginians have lost coverage — roughly 15% of the over 1 million members whose cases have been reviewed so far.

For the past three years, anyone who was enrolled in Medicaid was allowed to keep their coverage regardless of whether or not they still met eligibility requirements like income level. Now that the COVID-19 federal public health emergency is over, the Department of Medical Assistance Services is carrying out a redetermination — or “unwinding” — process to decide which members no longer qualify.

DMAS Director Cheryl Roberts and Deputy of Administration Sarah Hatton told the House Appropriations Committee this week that there are three main reasons why enrollees are losing coverage: They have gotten access to insurance or higher income through a new job, they have transitioned to coverage through the federal marketplace or they have encountered procedural problems like not responding or submitting renewal packets to the state on time.

DMAS’ eligibility redetermination tracker indicates that 32% of people who have lost coverage in Virginia as of October lost it for procedural reasons rather than ineligibility.

Even though DMAS and the Department of Social Services have been planning for Medicaid redetermination since 2020, Roberts admitted Monday the process has been a learning curve, especially when coupled with the state’s Medicaid expansion in 2019.

“Most members had never went through a redetermination, and also because we had turnover at the localities, most workers had never done a redetermination,” Roberts said.

Hatton told the Mercury DMAS is working to reduce the amount of procedural terminations by coordinating with the health plans that call, text, email and send letters to enrollees two months before their renewal is due. Health plans also try to touch base with enrollees during a 90-day grace period following their coverage termination.

DMAS Public Relations Coordinator Mary Olivia Rentner told the Mercury enrollees can fill out the renewal packet on their CommonHelp account online.

Additionally, Hatton said enrollees can call Cover VA to complete their renewal over the phone and check its status. Enrollees can also check their status by calling their local Department of Social Services. The department launched outreach campaigns a year before redetermination started to remind members to update their address and contact information, she noted.

“Across the country that’s one of the biggest concerns, is that we don’t know where folks are anymore,” Hatton said.

Hatton admitted there have been cases of mail delays where enrollees didn’t receive their renewal packets on time to submit them before their coverage ended. She also said she has heard of instances in which enrollees found out they no longer had coverage at a doctor’s appointment.

“For those individuals that are encountering that, call Cover VA,” Hatton said. “We can put them back, and we can even do coverage retroactive three months.”

The retroactive coverage — permitted in Virginia through a federal waiver — only applies to those who are still eligible for Medicaid.

There is also an escalation route to get quick assistance to people who need critical care like chemotherapy but weren’t aware their coverage ended, Hatton said.

Hatton said enrollees looking to check their redetermination date can call Cover VA or their provider. Enrollees are currently unable to check the date on their CommonHelp account online, as Hatton said the system is undergoing upgrades to make it more user friendly.

“It is the best practice for enrollees to call Cover VA to check their redetermination date,” Rentner said. “The state partnered with Medicaid providers to give them access to the redetermination date should a member ask for that information.”

Roberts emphasized that any member who has questions or needs assistance should call Cover VA.

Cover VA’s website is https://coverva.dmas.virginia.gov/ and phone number is 1-855-242-8282 (TTY: 1-888-221-1590) and language assistance services are available free of charge.

Photo via Online Marketing/Unsplash. This article was reported and written by the Virginia Mercury, and has been reprinted with permission.